[ad_1]

In the timeline of Michael Mann‘s career, his 1992 historical The Last of the Mohicans marked only his fourth of eleven feature films. Slotted six years after Manhunter and three before his breakout masterpiece Heat, the directorial touches now synonymous with a Mann venture were already in prime form (albeit through the lens of a more straightforward tale than his later subversive oeuvres): razor-sharp editing, meticulous action choreography, scenery filmed as intimately as a protagonist, and a nigh-unparalleled realistic virtuosity. Each trait is seamlessly embodied in the film’s final ten-minute sequence, uncoincidentally one of the most compact and affecting cinema endings in the thirty years since its release and a vivid blueprint forecasting Mann’s stylistic evolution.

What Is The Last of the Mohicans About?

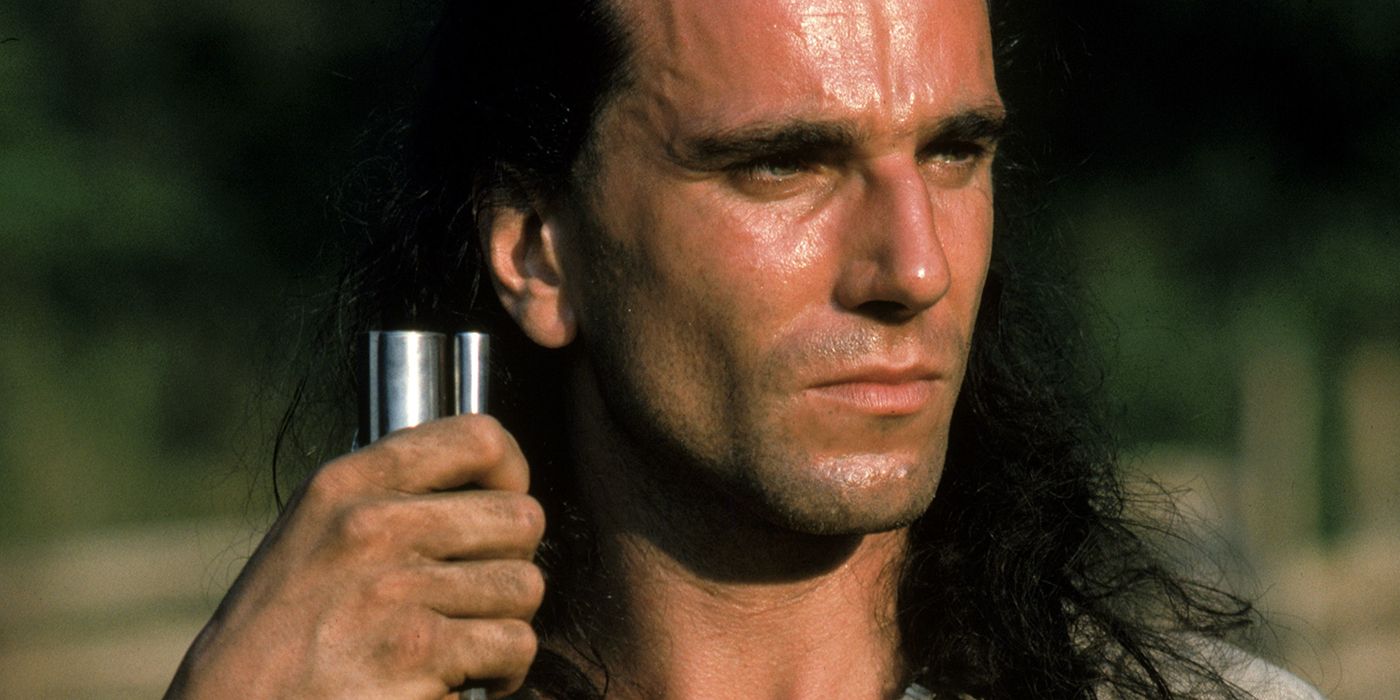

Based on the 1826 novel of the same name by James Fenimore Cooper, The Last of the Mohicans takes place during the Seven Years’ War and follows frontiersman Nathaniel “Hawkeye” Poe (Daniel Day-Lewis at his most dashing) as he escorts two sisters across upstate New York to reunite with their father, a British army colonel fighting off an invading French military in the Adirondack Mountains. Hawkeye is one-third of an inseparable trio led by his adoptive father, Chingachgook (Russell Means), and Chingachgook’s son, Uncas (Eric Schweig). As they evade an enemy group led by the vengeful warrior Magua (a truly arresting Wes Studi), Hawkeye falls in love with the elder Monro sister, Cora (Madeline Stowe), and the anti-establishment protagonist finally stumbles onto a cause worth fighting for. In a thematic move uncharacteristic for Mann, that cause is love: aka, the most ardent onscreen romance this side of Casablanca.

The film is an exhilarating accomplishment with captivating performances, majestic visuals, authentic costume and weapon reproductions, remarkable feats of production design, and a haunting emotional core that bites so viciously it’s hard not to feel exhausted when the credits roll. The loss of this fictionalized version of the Mohican people is a fraught, anti-imperialist cry for justice; Mann’s empathy is tangible. He just so happens to present the story as part of an all-you-can-eat buffet for fans of sweeping Revolutionary War-era romances.

Mohicans Was a Critical and Commercial Success

The film rightfully claimed the Academy Award for Best Sound, and feels equally timelines yet representative of the 1990s filmmaking era. Remember when crews shot on location before green screen dictated otherwise? That level of technical legitimacy has always helped Mann evoke a convincing atmosphere, most especially in a trilogy of set pieces from features across his career: Mohicans (obviously), the iconic Heat, and his neo-noir Collateral.

When Mohicans reaches its final ten minutes, Mann has already spent two hours laying down internal logic, cohesive character beats, and the danger presented by the frontier setting. They’re pieces of his puzzle, and all that’s left is the emotionally climatic finale: after Magua successfully captures the Monro daughters with murder on his mind, the lead of the Huron tribe instead orders Magua to take the quiet, sensitive Alice (Jodhi May) as his new wife. Magua storms off in fury while Uncas races after Magua in a desperate attempt to rescue Alice, the woman he loves from afar.

What unfolds next is the language of cinema in its purest form. As Uncas pursues Magua on his own while Chingachgook and Hawkeye feverishly trail a hair’s breadth behind, Mann jettisons all dialogue. With nothing else to draw the eye or ear, the bare-bones process of communicating art through a visual medium is left standing on its own strength. Cinematography, sound design, pacing, score, and the cast’s physical intensity together weave a silent poetry-in-motion. It’s a preemptive version of the same technique Mann would employ to outstanding effect in both Heat‘s legendary bank heist and the club assassination in Collateral.

Mann Is Beloved for his Details, Which Make the Movie

In Mohicans‘ breathless race against time, those minutiae begin by highlighting Hawkeye and Uncas’ labored breathing as they literally scale a mountain. The noises in Mann’s combat scenes always seem louder and more piercing than the average action movie and therefore more viscerally terrifying. Although here it’s crisp leaves crunching underfoot rather than machine guns on overdrive, when combined with shots of Uncas’ hands scrambling for purchase or the sweat staining Hawkeye’s throat as he single-handedly reloads his musket, it’s an authenticity that the audience instinctively accepts. Even when Magua (spoilers) ruthlessly murders Uncas, the arterial spray striking the rocks below is heard but unseen.

Heat’s Violence Follows the Same Pattern

Swapping the outdoors for an urban cityscape, Heat’s robbery follows the same pattern by grounding the audience’s spatial and situational awareness with establishing sounds as much as establishing shots. Hear the tapping footsteps of criminals Neil McCauley (Robert de Niro) and Chris Shiherlis (Val Kilmer) as they enter a bank lobby. Watch their eyes in close-up calculate a plan against a backdrop of humdrum office Walla. Ratcheting the tension higher is Elliot Goldenthal‘s deceptively simple soundtrack, a repeating pattern not dissimilar to McCauley’s stalking stride. The fact that de Niro and Kilmer carried the correct amount of spare magazines and knew how to use them adds yet another subconscious layer of slow-burn suspense – viewers understand this took true blue effort from the actors.

Thanks to that keen precision, when the mostly dialogue-less violence erupts, it’s volcanic. Obviously, any professional sound designer will mix an important effect loud enough for viewers to hear, but Shiherlis beating a guard is an auditory assault worthy of a flinch. And if inside the bank was a volcano, outside on the bustling Los Angeles streets is a supernova. Al Pacino’s LAPD detective Vincent Hanna has spent ages hunting these elusive thieves, but once Shiherlis sees officers waiting, the beaming Val Kilmer grin is instantly replaced by his rising gun.

The subsequent fight and its disastrous aftermath are continuous, overwhelming, and world-ending. And for good reason: Mann used the live audio of the combat-trained actors firing true rounds instead of the traditional method, where a foley artist replaces on-set audio. The legitimacy is searing.

Mann’s Influence Also Shows in His Films’ Editing

As for editing, even without music Heat boasts a rhythm by proxy thanks to co-editor Dov Hoenig (a repeat Mann collaborator, having also cut Mohicans). Hoenig switches back and forth between the opposing groups in time with bullet strikes. The entire sequence, an alternate universe echo of the Mohicans finale, is Mann easing his audience into a lived-in world before unrepentantly tearing away the rug. And Hoenig’s contribution in both cases can’t be overlooked – director and editor shared a vision and refined it film-to-film.

In comparison, Collateral’s impressive gunfight set in a Korean nightclub flips expectations like a gymnastics routine. The plot is straightforward but clever: Tom Cruise‘s unfairly stylish hitman, Vincent, kidnaps cab driver Max (Jamie Foxx) and forces him to chauffer Vincent around town while the latter carries out assassinations. If Heat’s sound design amplified the quiet normalcy of daily life, a deafeningly loud dance bop submerges the room like a wet blanket. The audience waits, and waits, before the pay-off when Vincent shifts from prowling hunter to lethal killer (recalling Shiherlis in the bank). The ghastly snaps of twisting necks are leveled loud enough to feel explosive, and when the live round double taps inevitably fly, they shred right through a once-raucous song. In tandem, editors Jim Miller and Paul Rubel capture the chaos of a midnight bloodbath without losing spatial awareness of a dozen or more players. Through a simple twist on his own post-production method, Mann conducts a narrative with mastery.

In a Michael Mann Film, Every Shot Has Significance

Every shot in his films has significance, whether it’s Heat and Mohicans cinematographer Dante Spinotti tinting the lonely scope of Los Angeles blue or implying that mankind is inconsequential with a pan over the fog-soaked Blue Ridge mountains. Every cut has significance, Hoenig balancing with ease separate but simultaneously moving groups in not one, but two films.

Even Mohicans‘s glorious final track, “Promentory,” soars best when paired with Hawkeye flying down forested mountain trails. The score’s Celtic violin refrain is as unrelenting as the heroes’ pursuit and as inescapable as the unfolding tragedy. As a grief-stricken Chingachgook raises his weapon against Magua, Hoenig cuts to three different angles in tandem with the beat. It’s a fundamental editing technique used to increase the impact of a blow, but it feels like the music rises in triumph as Magua meets his demise on the crest of the highest note.

There’s a transcendent grace to Mann’s depiction of onscreen violence. As such, critics have dubbed Mohicans as the least “Mann-like” film because of its clean, traditionalist story focused on romantic and familial ties. It’s true, but doesn’t that make the connective tissue it shares with his future works even more interesting? Whether his films offer a nihilist outlook or a silver of hope, Michael Mann’s progression into one of the 20th century’s landmark directors began with a silent, domed race across the mountains.

[ad_2]

Source link

Armessa Movie News