[ad_1]

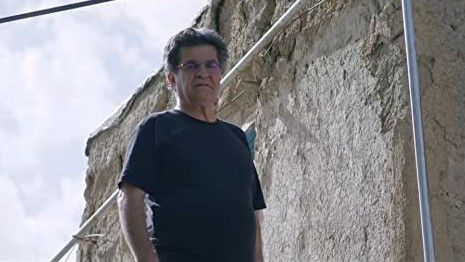

Movies have such tremendous power. They can instill so much emotion in the viewer and make them feel less alone in the world. That power can also be used in a subversive manner and to challenge the status quo. Few people understand this truth quite like director Jafar Panahi. In 2010, after being sentenced by the Iranian court system Islamic Revolutionary Court to a 20-year ban on directing movies (in response to Panahi creating documentaries that highlighted problems in Iran society), Panahi secretly helmed This Is Not a Film. This was a documentary that captured the filmmaker under house arrest and ruminated on the filmmaking process. This is Not a Film wasn’t just a movie, but a rebuke against the suppression of his creative voice. There was something innately dangerous about his work.

In July 2022, Panahi was arrested and sentenced to a new six-year jail sentence. Before he was imprisoned, he finished a new movie, No Bears, that is currently unspooling in North American movie theaters. Within this feature, Panahi once again contemplates the tremendous power of videos, photography, and filmmaking as an art form.

The Initial Presence of Filmmaking in ‘No Bears’

Much like This Is Not a Film, Panahi is the central subject of No Bears, though this time it’s in the confines of a fictional narrative drama rather than a documentary. Shifting gears like this doesn’t undercut how No Bears is drawn directly from the experiences of Panahi as an artist. As the movie begins, we see Panahi directing a movie in the bustling streets of an Iranian city via Zoom. Just like in real life, this version of Panahi is restricted on where he can and cannot go, but that doesn’t deter him from exciting new artistic pursuits.

Panahi is living in a small village that’s paranoid about being photographed. At one point, Panahi strolls outside with his camera and talks to an elderly lady neighbor, who insists that she not be photographed by Panahi. Both of the people in this scene are aware of the power of photography or videos. They can be used for evil purposes, but they can also be used to reaffirm the very existence of people that powerful institutions and governments want to silence or wipe out. Panahi stands firm in the face of those hardships. This elderly woman, meanwhile, embodies the detachment many of these villagers have toward photographic art. They see it as merely a way to stir up trouble rather than challenging corruption.

The power one photograph can wield is reinforced when the primary dramatic thrust of No Bears kicks in, which concerns this village being convinced that Panahi took a photograph that captured the engaged Gozal (Darya Alei) and another man that isn’t her husband, Solduz (Amir Davar), embracing one another. Panahi insists that he didn’t do it, but since he’s perceived as taking a photograph that disrupts a long-established marriage arrangement, this director is turned into a pariah. Panahi is experiencing firsthand how much power photographs wield, as well as how quickly lies spread about himself and others, like Solduz (who’s characterized by many as a ne’er-do-well, but in his conversation with Panahi, comes across as a socially conscious man).

This entire storyline reflects Panahi’s real life in a tragically fascinating way by reminding viewers who society and its citizens tend to demonize. Rather than confronting problems or disgruntled emotions, human beings have a tendency to make a villain out of those drawing attention to societal woes. Panahi in No Bears is made out to be a scheming villain just because of the notion that he holds evidence of an event that would break a tradition. The thought process behind these villages is that suppressing Panahi and removing the photo would also erase any problems entirely. It’s all a microcosm of how Panahi’s works highlighting systemic issues in Iran tend to draw far more controversy as works of art than the systemic issues they highlight.

This leads to another key part of how No Bears explores the power of filmed and photographic media: the truth. When we’re watching a movie or even looking at a photograph somebody snapshotted, we’re assuming that what we’re seeing is the 100% unvarnished truth. If a film shows somebody eating a lot of BLTs or listening to a lot of A Tribe Called Quest albums, we presume they like those things, Those elements become part of the assumed truth of the frame. This is what makes features with unreliable narrators or photographs intentionally warped with filters so exciting. They’re playing on our assumptions that what we see in each frame is true. This trait of photography or video art can be twisted by, among countless other terrifying purposes, those making propaganda trying to demonize marginalized groups.

Panahi’s works and personal life, meanwhile, have been fixated on using the art of film to emphasize silenced truths.

How Filmmaking Can Play Into the Truth

Panahi’s status in Iranian society has stemmed from his unwavering attempts to capture the truth of reality in Iranian society on film. His earlier features, The Circle and Offside, were about putting his country’s cruel treatment of women front-and-center in the frame. These productions, though narrative features rather than documentaries, were so in tune with the brutal realities of the country they were created in that they were banned in Iran. His secretive documentaries, like This Is Not a Film or even his segment in The Year of the Everlasting Storm, hinge entirely on capturing intimate facets of his day-to-day existence.

No wonder, then, that the concept of the truth and how filmmaking can salvage it plays so deeply into No Bears. Backed against the wall, Panahi sees filmmaking as a tool to utilize when the rest of the world becomes entrenched in deception.

This gets exemplified by a late scene in which Panahi is pressured to speak in a sacred Swear Room that he never took that photograph of Gozal and Solduz. Doing so will alleviate the minds of the villagers that keep accusing him of being untrustworthy. However, Panahi is later told rather nonchalantly that he can totally lie in the Swear Room if he wants to, it’s no biggie. Even in these confines built on conveying the truth, lies can fester. Panahi eventually goes to the Swear Room, but he brings with him a camera and a tripod to record his testimony. In a place epitomizing societally sanctioned lies, Panahi is using the tools at his disposal to capture his truth, his words, his existence.

The exploration of truthfulness and other aspects of filmmaking is not just limited to sequences centered on Panahi. No Bears also makes time for a subplot involving actors in Panahi’s film, Bakhtiar (Bakhtiar Panjei) and Zara (Mina Kavani). Midway through the movie, Bakhtiar goes to a meeting with a smuggler for a passport, an interaction Panahi insists on recording. At this rendezvous, the smuggler, much like the elderly lady neighbor, insists on not being recorded while he and Bakhtiar turn their backs to the cameras when they’re talking. If their lips aren’t seen saying certain dangerous words on-camera, it’s as if their conversation doesn’t exist. This smuggler is also aware of the power of recording and how, much like that Gozal/Solduz photograph impacted Panahi’s life, could turn his entire existence around.

Is There Truth in Filmmaking?

The presence of filmmaking in the storyline involving Bakhtiar and Zara reaches its most compelling point when the duo appears to be saying goodbye, new passports in hand, ready to start a new life…when Zara breaks the fourth wall. She begins speaking to Panahi directly and questioning the authenticity of the scene they’re filming. She tears off her wig and grabs Bakhtiar’s passport, revealing it to be a fake. She begins criticizing Panahi for creating a cinematic domain meant to appease his mind more than create something truly authentic. Even Panahi’s best intentions cannot ward off the sense of inauthenticity that creeps into so much of our world. Zara concludes her captivating monologue by unforgettably proclaiming “we all become fake here!” She could just as well be talking about Iranian society, the Western world, or so many other parts of the planet Earth beyond just Panahi’s film set.

Throughout No Bears, Panahi exhibits hopefulness that filmmaking can be used to cling to the truth in a sea of lies. But this sequence sees the director looking inward and wondering if filmmaking as an art form can accomplish these lofty goals. Even the medium of documentary cinema, a format of cinematic storytelling meant to capture the truth, is built on the back of projects like Nanook of the North, which are nothing but harmful lies. Perhaps this avenue of artistic expression is always prone to falsehoods or contradictory elements innate to anyone expressing their subjective view of the world.

With this sequence, Panahi lends a nuanced look to filmmaking. He is not here to make a hagiographic ode to the art form, and he always puts the experiences of human beings at the forefront of his work. That latter element is made apparent in the final scenes of No Bears, which chronicle two separate instances of people being overwhelmed with grief over discovering the corpse of a loved one. Both of these scenes are captured in wide shots, with the body being only a small part of the frame. In one scene, a single man sobbing over the loss of his wife is also a prominent part of the frame while the other features hordes of people expressing similarly pronounced expressions of woe over the death of a child.

These are senseless, pointless deaths. The camera is now being used to capture a very important truth: the impact death has on others. There’s a harrowing quality to these sequences as we forget about the very act of filmmaking itself due to the absorbing emotionality of these events. Paradoxically, that feat speaks to the importance of filmmaking, even while the viewer and No Bears as a feature are cognizant of the flaws ingrained into this practice that Zara highlighted. Two fictional people are dead by the end of No Bears, but the camera is capturing how their lives are still impacting people while prior footage of these characters alive and well allows them to be eternal to some degree. All of that is contained just through images captured on a camera.

There’s a reason the sheriff of the village Panahi is staying at in No Bears was so determined to get that photograph.

There’s a reason Panahi had to get creative with getting movies like This Is Not a Film out of Iran.

There’s a reason Panahi has been arrested multiple times.

Films have power and all that power comes from the people in front of the fame and wielding it. In the proper hands, films can highlight injustices governments would rather act like never happened, and they can serve as reminders that certain people are enduring in the face of adversity. People can “become fake” in the frame of a movie and Panahi is incredibly cognizant of that aspect of cinema, photography, and the process of filmmaking. But these tools still wield a lot of usefulness in our world. This theme would’ve been incredibly important under any circumstances. However, in the wake of Panahi being behind bars again, the core ideas of No Bears and the best ways people can utilize filmmaking are more urgently essential than ever.

[ad_2]

Source link

Armessa Movie News