[ad_1]

While the FBI may have been recently up in arms over the controversial eco-thriller How to Blow Up a Pipeline, their involvement and concern over Hollywood cinema is nothing new, as seen with Jules Dassin’s Uptight, a 1968 film about black militancy that the Federal Bureau of Investigation went so far as to plant informants on set for. While not as remembered or celebrated as some of Jules Dassin’s other classics, its production history certainly qualifies it as among the most interesting, especially given that Uptight (sometimes stylized with a provocative exclamation point at the end) was not originally supposed to be as pointed of a statement as it would later become. So, what exactly was it about the film that had the FBI so concerned from day one?

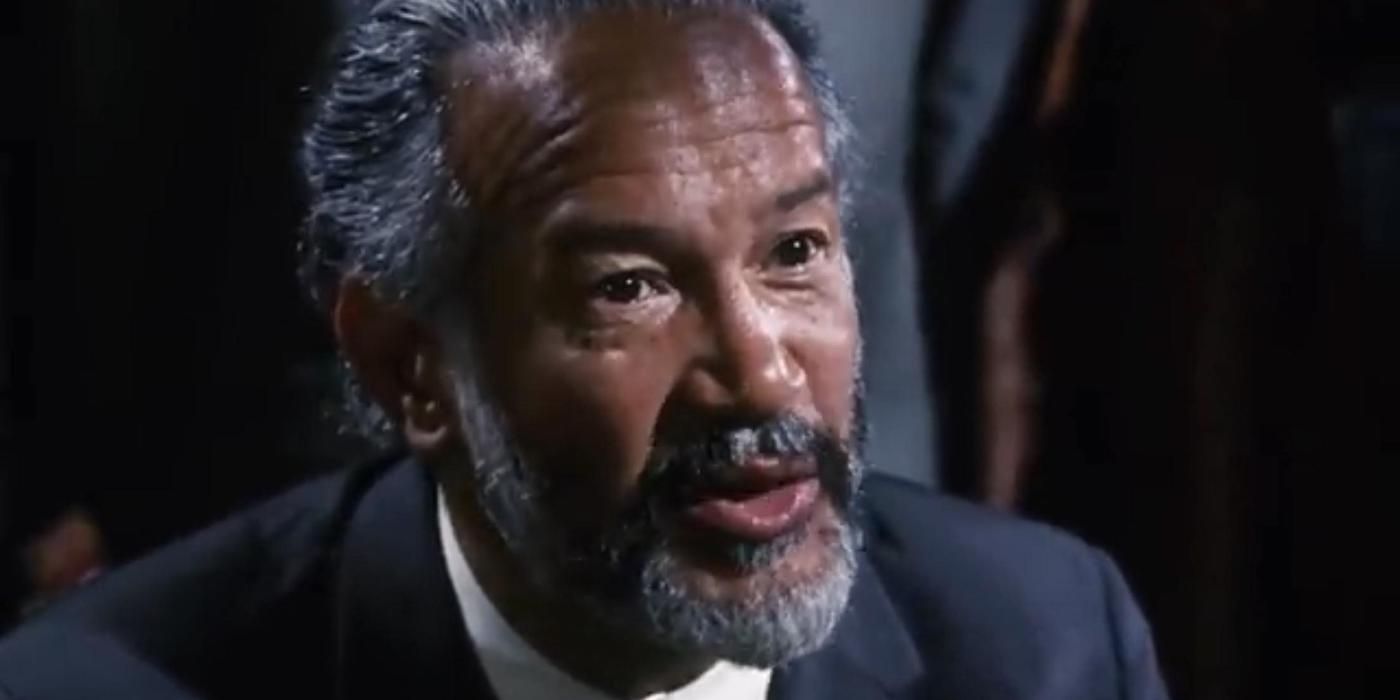

The film stars Julian Mayfield in the role of Tank, an alcoholic MLK advocate (in that he supported non-violence in contrast to his more militant brothers) who’s unable to find a job after being released from prison for striking a white co-worker at a steel mill after he harassed his Black colleagues. Unable to find work, his alcoholism and erratic behavior causes him to miss out on a mission with his revolutionary group to steal guns from a warehouse in preparation for a potential race war. As a result of being a man short, his brother Johnny (a revolutionary icon among his peers, played by Max Julien) is forced on the run due to his killing of a white security guard. The rest of the film follows Tank’s exile from the revolutionary group, leading him to rat out Johnny to collect the police’s cash reward.

How Did ‘Uptight’ Incorporate MLK’s Assassination?

Uptight was released in December 1968, the very same year that Martin Luther King, Jr. was ruthlessly assassinated, and that is by no means a coincidence. Most impressively, the film manages to incorporate the non-violent cultural leader’s assassination into the backdrop of its main events, encapsulating the fear and pain of the Black community in the wake of one of their great leader’s untimely deaths. However, the film was originally conceived by Dassin as an adaptation of Liam O’Flaherty’s 1925 novel The Informer, the likes of which was made into a film in 1935 by none other than John Ford (nabbing the director his first Academy Award for Best Director at the 8th Academy Awards). While the source material primarily concerns the Irish Civil War, Jules Dassin intended to update the setting from Dublin to Cleveland, possibly informed by the election of the city’s first Black mayor, Carl Stokes.

That the script was in a state of constant revision is an understatement, as MLK’s assassination occurred after Dassin had completed most of the film’s production. Far from content to go back to the drawing board, as no movie about Black revolutionaries could be released in the climate without exploring an event so earth-shatteringly current, Dassin wrangled his crew to gather documentary footage of King’s funeral in Memphis and Baltimore, weaving it into his film in an editing room in Paris to evade threats from Paramount to suppress the film’s revolutionary ideals. The result directly reflects the climate. The ultimate preacher of non-violence and forgiveness was ultimately met with violence, so what are his followers expected to do but react violently in return?

What Does ‘Uptight’ Get Right about 1960s Black Militancy?

As a result of the civil rights leader’s assassination, the militarism on display in Uptight was enhanced, with the revolutionaries it depicts in constant debate over their progressively violent intentions. With the screenplay jointly written by Dassin and his stars, Mayfield and Ruby Dee, all activists and intellectuals alike, the film wasn’t just well-researched but wildly authentic to the experience of Black Americans of the time, showcasing the damage that MLK’s assassination had to the idea of non-violence as an effective means of protest. One white character is exiled from the revolutionary group in spite of his status as a long-time supporter of the cause, while the Black leaders (headed by B.G., played by Raymond St. Jacques of Rawhide fame) refrain from sugarcoating their intentions to violently oppose their white oppressors.

Much of the film is centered around debates among the revolutionaries over the extent to which violence is justified against oppression, recalling The Battle of Algiers, a film that came out just two years prior that was so bold in its depiction of a violent revolution that the Black Panthers and the IRA both adapted it into training manuals. Heavily informed by the postcolonial theories of psychologist and political philosopher Frantz Fanon, both The Battle of Algiers and Uptight remain prominent examples of films that argue the case for violence in the face of violence. While wildly controversial, revolutionary leader Malcolm X makes a compelling argument in his autobiography, in which he states: “I believe it’s a crime for anyone being brutalized to continue to accept that brutality without doing something to defend himself,” arguing that violence in the face of brutality isn’t violence, but self-defense.

The FBI Closely Monitored ‘Uptight’s Production Process

Though the Communist suspicions of this production’s writers meant that those involved (Mayfield in particular) were already on the FBI’s watch list (never mind that the source material’s writer O’Flaherty was a founding member of the Communist Party of Ireland, though that didn’t stop Ford from adapting his work), the bureau got serious after getting their hands on the “dangerous and subversive” screenplay. In addition, rumors spread of the production paying $2,000 a day to the Black Panther Party for protection, some of which was further rumored to buy them weapons. If there’s any contention that Uptight deserves a making-of documentary on par with Hearts of Darkness and Burden of Dreams, let it end here, because the story just gets crazier.

Concerned the film would exacerbate existing tensions among the Black community and potentially ignite race riots, the bureau leaked the screenplay to a local journalist and orchestrated mounting tensions between the local police and the film’s extras (local Black militants), forcing Dassin to cease filming in Cleveland and head for the Paramount lot in Culver City. According to author Christopher Sieving in Soul-Searching: Black-Themed Cinema from the March on Washington to the Rise of Blaxploitation, the set was carefully monitored by carefully planted informants from the studio, with memos of concern traced back directly to bureau director J. Edgar Hoover himself. The irony of a film about an informant actually having informants on set isn’t so much a coincidence as it is a testament to the subject matter and the bravura it took to complete and release the film within such a critical time frame, reflecting its extreme contemporary urgency.

With a production history so richly controversial, it’s worth noting that the film itself is a stunning accomplishment regardless of its tumultuous production. As the Oscar-nominated director of Rififi, commonly regarded as one of the greatest heist movies of all time, as well as the iconic Greek romantic comedy Never On Sunday, Dassin is a master of both formalism and emotion. Uptight has the psychedelic imagery that epitomizes the best of the iconic sixties aesthetic (one funhouse scene, in particular, offers an incredibly inventive use of mirrors to reflect Tank’s warped psychology), with a jaw-dropping animated title sequence and a soundtrack by none other than soul/funk legends Booker T. and the M.G.’s. Despite its nigh-forgotten status, it’s a radical film in every regard and deserves to be celebrated among the best of American revolutionary cinema.

[ad_2]

Source link

Armessa Movie News